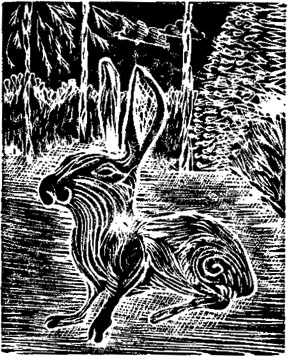

Figures above: The top detail is an example of metal engraving illustration. The bottom is a detail of wood engraving illustration from the same book. In these enlargements, the difference between the two engraving and printing processes becomes clear: in the top example, a very sharp, small blade was used to incise the lines, which vary in width at the entrance and exit points; in the bottom example, the lines are the result of material having been cut away from the wood’s surface and do not taper but begin and end more abruptly. John Clark Ridpath, Cyclopaedia of Universal History (Cincinnati: Jones Brothers Publishing Co., 1885).

#ThrowbackThursdays

History is vital and important. In this series, Nancy Sharon Collins, design history aficionado will expound upon design history, one Thursday a month, in essays that throw you back in time to learn and understand design’s roots as an industry and design thinking and theory.

This month, Nancy discusses the art of engraving and the difference between metal and wood engraving.

It is important to illustrate the distinction between engravings created by cutting into copper or steel and those made with wood because it is easy to confuse the two processes. In fact, they are entirely different technologies that produce extremely different effects creating illustrations for printed medium. So, for any student of graphic design history, or for those curious about the history of printing, this distinction is crucial.

In old-fashioned, as well as new-fangled popular culture, many fine books, magazine articles, websites and blogs covered the subject of wood engraving and wood block printing, but metal engraving has become somewhat of a shy, second-cousin to those processes. Why? There is just more wood engraving, and wood cut, out there; everybody and their monkey‘s uncle seem to have a stake in some form of letterpress or relief printing. Generally speaking, this is because learning to engrave on wood is a lot easier than mastering the less-forgiving surfaces of copper and steel. Make no mistake, becoming expert at fine wood engraving is itself an art form; however, wood is easier to work with and much more compatible with industrial printing than its less popular sibling, copper or steel engraving. [i]

Figure above: Contemporary example of woodblock printing by Emily DeLorge, Houma, Louisiana, 2011.

Carving on wood to make prints is the oldest print making method known. “Some six centuries after the invention of the wood block in the East…the craft was developed in Europe, in about 1400…Every part of the wood surface was [then] removed except the lines of the images…When the block was completed, the image stood up as a level surface in relief.” [ii] Also referred to as xylography, early printing was done on the plank, or long side of a piece of wood that provided a lot of surface area on which to draw and cut. Think of cutting up a carrot lengthwise, to make sticks. It’s as easy as peeling the carrot because you are cutting along the same direction as the fibers, or grain.

Figure above: The Springer, or Cocker, wood engraving by Thomas Bewick (1753–1828). Bewick, perhaps the most famous wood engraver, is credited with popularizing the use of end-grain specimens of boxwood, a specific species of wood that allowed for greater detail, longevity, and longer press runs. The hard surface of end-grain wood can generate more print impressions than the softer, long-grain wood (the long side of a plank of wood), which was traditionally used for woodcut printing. Bewick greatly influenced the development of illustrated book production because the finer, sharper tools used in metal engraving could be used on end-grain wood, allowing for minute detail previously achieved only in metal. As with wood block, wood engraving could be made type high which meant pictures and text could be composed and printed together rather than in a separate, and costly, second press run which still had to be done in metal engravings. John Rayner, A Selection of Engravings on Wood by Thomas Bewick (London and New York: Penguin Books, 1947). Thomas Bewick, perhaps the most famous wood engraver c1753-1828, is credited with popularizing the use of “end-grain” pieces of a very specific type of wood (boxwood), allowing finer detail and longer press runs. Again, using the carrot analogy, end-grain carrot slices would be cut cross-wise producing little wheels; this method is cut across the grain or fiber. Cross-grain surfaces are much stronger than long grain. Cross, or end-grain, “matrices” will produce many more print impressions than the softer, long-grain matrix. [iii]

Figure above: Thomas Bewick, Newfoundland Dog. John Rayner, A Selection of Engravings on Wood by Thomas Bewick (London and New York: Penguin Books, 1947).

“Bewick did not invent boxwood engraving as such, but he developed techniques of drawing, cutting and printing which attracted much attention. It led to a new phenomenon, popular illustrated books, where letterpress text and engraved woodblock could be set into the printer’s form and printed together. This process dramatically reduced production time (and, therefore, publication costs) and changed the appearance of the printed page. [i] This technique went on to dominate nineteenth century illustrated book production.” [ii]

End-grain wood was revolutionary, too, because the super-accurate tools used in copper plate engraving could also be used on boxwood, allowing for amazingly minute detail previously thought only to be achievable in metal. “The history of nineteenth-century printing is intimately bound up with the engraved boxwood block, the single most significant piece of illustration technology, which dominated early Victorian book illustration. The first book to be so illustrated was Thomas Bewick’s The General History of Quadrupeds (1790). The artist engraved his own white line illustrations on boxwood blocks, and the artist-engraver remained a common figure in book illustration until mid-century.” [iii]

The notion of “white line” was new; heretofore, engraved lines were cut to be black (or as a positive image). For each “line” in a composition, a cut is made that holds ink (this is intaglio). Conversely, in white line engraving, all of the white areas are removed by cutting the wood away, leaving only the high, original surface to transfer ink (this is the relief process). An easy way to think about this is the belly-button analogy: engraving (intaglio) is an innie and wood cut (relief) is an outie. Letterpress is also a relief process, which is why the advent of wood engraving on type high matrices was such a revolutionary invention. [iv]

This article is the second in an ongoing series about graphic design history by Nancy Sharon Collins, stationery extraordinaire, and AIGA New Orleans chapter special projects director. Here Collins excerpts her recent book published by Princeton Architectural Press, The Complete Engraver.

[i] See AIGA New Orleans chapter website article, “Engraving, type, monograms and the history of graphic design.”

[ii] Bamber Gascoigne, How to Identify Prints. A Complete guide to manual and mechanical processes from woodcut to ink-jet. (New York: Thames and Hudson Inc., 1986).

[iii] In this context, “matrix” is the piece of wood upon which a design is cut to make a wood block, or wood engraving, print.

[iv] Prior to this, illustrations would usually be printed at a separate time on a separate press that could leave a plate mark or visual indication that the picture was a non-integrated element of the letterpress process.

[v] The Bewick Society website, “Technical Background” page. Retrieved May 19, 2011. http://www.bewicksociety.org/galleries/techniques.html.

[vi] The Victorian Web, literature, history, & culture in the age of Victoria, “The Technologies of Nineteenth-Century Illustration: Woodblock Engraving, Steel Engraving, and Other Processes”. Retrieved May 19, 2011. http://www.victorianweb.org/art/illustration/tech1.html

[vii] “Type high” is the height of a block of letterpress type.

|

By Nancy Sharon Collins

Published April 24, 2014

|